Nestle, like most consumer packaged goods companies, has a strong Sustainability program, and as a European company has perhaps been at it for longer than many of its US counterparts.

There is just one problem – environmentalists hate its bottled water.

For years, Nestle benefited from the long surge in bottled water sales, achieving double digit annual growth with such brands as Perrier, San Pellegrino, Pure Life and Poland Springs. In 2009, Nestlé’s market share was 38% of the $10 billion US bottled water market.

“Water is a category that gave us so many years of joy,” Nestle CEO Paul Bulcke told the Wall Street Journal this week. “And all of a sudden, it changes. That is what hurts.”

The tale of Nestle and bottled water should be a cautionary tale for many companies pushing Sustainability agendas – be careful what you (publicly at least) wish for.

Bottled water has increasingly become a target of a variety of environmental groups, who argue that the environmental impact of bottling the water in factories, manufacturing the plastic containers it comes in, and transporting it to stores is not worth the “added value” of bottled water versus tap water or other alternatives.

Whether it is Green concerns or the realization that bottled water is very expensive versus the alternatives amid tough economic times, the former rapid growth is now gone for the category.

Numerous sources continually finger bottled water as an environmental bad guy. Some have accused bottled water manufacturers of lying about the environmental impact of its products, or about the differences between bottled water and plain tap. Many restaurants have stopped serving bottled water for environmental reasons.

That and more have led the bottled water category to take some hits. Some consumers dramatically cut back on bottled water purchases altogether. Those consumers who kept buying often started trading down to more generic brands, hurting the high end brands such as those owned by Nestle.

Nestle’s bottled water sales fell by more than $4 billion world wide in 2009, or some 13%, putting a huge dent in Nestle’s bottom line.

Environmental Gymnastics

In response, Nestle is pursuing a variety of environmental and PR offenses to get itself of the Sustainability prime target list.

For example, to tap into one natural spring to use for its bottled products, Nestle is currently attempting to prove there will be no harm to endangered Sockeye fish being raised in an Oregon hatchery that would have to switch to municipal water as Nestle siphoned off the spring. The year long test is under lock and key over concerns environmentalists might try to contaminate the hatchery water.

“We are accused of mining water, which would suggest we are depleting a resource,” says Kim Jeffrey, CEO of Nestle’s US bottled water business. “But instead, we take water in an environmentally sustainable way.”

In this plan for “Cascade Locks,” Nestle would pay to pump municipal water into the Sockeye hatchery at a level that would completely replace the water the Sockeye facility currently takes from the spring.

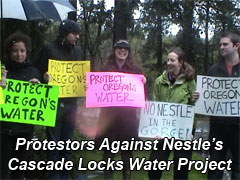

A variety of environmental groups have formed in Oregon to oppose the effort, which would bring jobs to the region, and have united under the theme of “Keep Nestle Out of the Gorge,” referring to the local river valley not far from Mount Hood.

Other environmental groups accuse Nestle of specifically looking for springs in economically challenged areas, a charge Nestle denies. One environmental challenger says Nestle only winds up paying well less than one cent a gallon for its water sources, while selling that same water for as much as $5.30 per gallon. Nestle says at the low end the retail price for spring water is $1.20 per gallon, and that bottling and logistics costs easily explain the cost differences.

Today Nestle – maybe tomorrow your business?

In fact, what started out as a market advantage to Nestle – the fact that is primarily used natural spring waters for its products, has now often turned into an environmental liability. Some 80% of Nestlé’s bottled water comes from such “natural” sources, which can have consumer appeal, whereas many of its competitors source most of their water from municipal sources. In fact, what started out as a market advantage to Nestle – the fact that is primarily used natural spring waters for its products, has now often turned into an environmental liability. Some 80% of Nestlé’s bottled water comes from such “natural” sources, which can have consumer appeal, whereas many of its competitors source most of their water from municipal sources.

This “water mining” charge has plagued Nestle in recent years. It recently gave up on plans to tap into a Glacier-fed spring in Northern California after fierce environmental resistance. After a long battle, it did win the right to use a natural water source in Colorado – after agreeing to 44 different conditions for its use.

Another challenge is that potential natural sources can run contrary to Nestle’s other environmental initiatives. Nestle has cut its average delivery miles by some 15% over the last few years, for example. Some water sources don’t make the final cut for development – usually meaning a bottling plant nearby – due to such Green supply chain concerns.

Some locals in Oregon see the other side of the coin, however.

“The is becoming the battle of Middle Gorge,” the local mayor said of the Cascade Locks project. “Stopping Nestle won’t save the planet, but getting Nestle to come here could save the town.”

What is your take on Nestlé’s water challenges? Do you think other consumer goods or other companies could find themselves in business danger from environmental efforts? What might be the next “bottled water.” Let us know your thoughts at the Feedback button below.

TheGreenSupplyChain.com is now Twittering! Follow us at www.twitter.com/greenscm

|